NEW YORK (Reuters) - Kidnapping is the biggest nightmare of every Western journalist in Iraq but both foreign and Iraqi reporters face many other obstacles that obscure the U.S. public's understanding of the war.

Jill Carroll, an American freelance journalist missing in Iraq, was the 36th reporter to be kidnapped since April 2004, according to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists. Six of them have been killed.

"This has been our No. 1 threat and our worst nightmare for almost two years," Jackie Spinner, a Washington Post reporter who escaped a kidnap bid outside Abu Ghraib prison in June 2004, told Reuters.

"They grabbed me as I was walking out," she said. "I was wearing a scarf and an abaya. One man grabbed my wrist and another grabbed my waist and they started dragging me off."

Fortunately, U.S. Marines noticed and came to the rescue.

She recounts the incident in her book "Tell Them I Didn't Cry," due out on Feb 1. The book describes Spinner's experience reporting, including the 2004 siege of Falluja. But much of it is about her Iraqi colleagues, from drivers to cooks, guards and translators, and about how much she depended on them.

Most foreign journalists live and work outside the U.S.-controlled "Green Zone" but they do generally operate inside protected compounds, with blast walls and armed guards.

IRAQIS THE EYES AND EARS

At least major organizations like The Washington Post, The New York Times and Reuters have the resources to rely on networks of such Iraqis to be their eyes and ears on ground too dangerous for foreigners to tread.

"We're probably getting about 80 to 90 percent of the story because we're able to use Iraqis to help us," Spinner said.

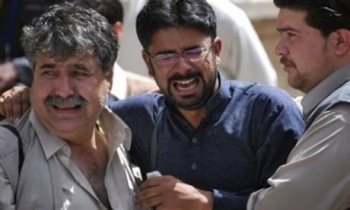

Iraqis may be less at risk than Westerners in the same situation, but they face huge dangers and many more have died.

Dozens of bombs explode every day, killing indiscriminately, and nervous guards at checkpoints open fire at the slightest suspicion. At least 60 journalists have died on duty in Iraq since the U.S.-led invasion in March 2003, of whom 41 were Iraqis. Insurgent action was the cause of 36 deaths while U.S. fire killed 13, according to CPJ figures.

U.S. forces acknowledge killing three Reuters journalists, but say the soldiers were justified in opening fire.

Some reporters have been targeted by insurgents for working with American companies and at least a dozen have been detained by U.S. forces suspicious of their activities, or even just the images on their cameras, the CPJ says. "They're held for months at a time, never charged," CPJ director Ann Cooper said.

"There's no due process and it's setting a terrible example in a country where the United States' goal supposedly is to establish democracy," Cooper told Reuters.

A Reuters cameraman was released on Sunday after being held for nearly eight months without charge, a week after two other Iraqis working for Reuters were released after months in jail.

BIG HOLES IN THE PICTURE

The dire security situation combined with unwillingness by U.S. publishers and editors to give space to in-depth reports means there are giant gaps in the picture seen by the American public, said Orville Schell, dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Berkeley.

"I don't think there's ever been such a difficult situation, with the possible exception of Moscow or Beijing during the height of the Cold War," Schell said. He added that U.S. TV news media in particular were doing an "abysmal job."

Greg Mitchell, editor of the industry newspaper Editor & Publisher, said Americans were not getting the answers to key questions such as how much local support exists for insurgents, particularly for foreign fighters linked to al Qaeda.

"What reporters can't or won't do is get close enough to really get a sense of what the average person feels or how this insurgency operates. We see the dramatic results but we just don't know how it works," Mitchell said.

He said all but the biggest U.S. papers were almost entirely dependent on news agencies such as Reuters and The Associated Press, because very few have correspondents in Iraq.

"There really has not been much independent reporting and here Jill Carroll was trying to do it and she gets kidnapped."

Tom Rosenstiel, director of the Project for Excellence in Journalism, said there was a danger of being blinded to the bigger picture by daily violence. "Do you not cover today's car bombing because you want to do a longer piece about the return of the agricultural economy?" he said.

"Reporters say: 'We're accused of covering too much bad news.' But how do you ignore a car bombing that kills 70 people just because you did one a week earlier?"'