In Honduras, the political condition is so bad that criminals are able to kill journalists freely with no worries. In a matter of weeks, seven journalists have been murdered and the Honduran authorities have been tardy in their attempts in pursuing the killers.

Spanning from the beginning of March till mid June, seven murders is a disconcerting count during such a short time in a country with a population of just 7.5 million. With most of the murders being clear assassinations carried out by hit men, journalists are running scared wondering who is going to be their next target.

A government official though, has responded to the killings.” I guarantee that in all of them there is nothing to indicate that it is because of their journalistic work,” Minister of Security Óscar Álvarez was quoted saying, asserting that the crimes were of regular street crime levels.

However, many journalists fear for the worst claiming that the murders have been conducted with the approval of police, armed forces, or even other authorities. This concern is fuelled by the breakdown in society that followed the June 2009 coup. Since then, journalists and other critics have reported repression that has included violent attacks.

A Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) investigation has found evidence that the victims in at least three cases were murdered in relation to journalism, and that work-related motives could have played roles in the others. The investigation also found that the murders occurred in a politically charged atmosphere of violence and lawlessness. The government’s ongoing failure to successfully investigate crimes against journalists and other critics whether by intention, impotence, or incompetence has created a climate of pervasive impunity.

The condition has worsened so much that Víctor Jiménez, manager of a radio station has described the state of affairs in Honduras thus, “Narcotics gangs now are stronger than the government. The powerful families that have been running parts of this country for generations, some of the politicians who have personal power, local military leaders—all of them work outside of the government’s power. The government is on the margin, it has the least power. That is why we have legal impunity, because the police and the courts don’t mean anything. The people won’t talk to them; the people are afraid of the real power.”

A Latin American diplomat who deals closely with the Honduran government put it this way: “What I see is an organized effort by private groups to repress opponents—social leaders and journalists. Not a plan by the government, but something the government can’t control or maybe doesn’t want to control. It is these powerful private groups that could be threatening and killing for political and commercial reasons.” The diplomat, who asked for anonymity to protect continuing relations with Honduras, said general lawlessness in the country serves the purposes of a small elite class that wishes to advance its business and political interests without being subjected to societal scrutiny.

Presidential elections in November 2009 brought the conservative Porfirio “Pepe” Lobo to power. Although many, mainly supporters of ousted President Manuel Zelaya, decried the vote as the handiwork of an illegal regime, the new government was accepted by the United States and a number of other nations.

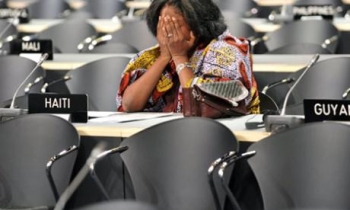

While the US directly pressured Lobo’s Honduras on the question of human rights, most countries in the Western hemisphere have used the Organisation of American States (OAS) to demand human rights reforms from the Honduran government. They have some leverage: Honduras has been seeking re-entry to the OAS after being expelled after the coup. Said one international diplomat stationed in Honduras: “It is certainly a major priority of the Lobo government to restore good relations with the OAS—and in that sense these cases of the journalists are very important.” The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the human rights arm of the OAS, issued a statement on May 19 expressing deep concern over continued human rights violations in Honduras, including the killings of journalists.

On June 4, finally awakening to the widely held perception that it was indifferent to anti-press crimes, the national government announced that it had asked for help from the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the US. Such help, though, is more symbolic than real. The FBI assigned one agent, who began work three months after the killings began, and often had only scant physical evidence and incomplete investigative reports to review. If the Honduran government wanted to change things, much more needs to be done, the CPJ report says.

As a result of the delay in investigations and failures in pursuing the criminals, the Honduran government has failed to do its duties like exerting necessary oversight over the national police, who are responsible for investigating these crimes. Over the long term, the legislature and executive branch have chosen not to allocate necessary resources and training to police, choices that have had entirely predictable results. Diplomats and journalists say police have also been infiltrated by criminal gangs, says CPJ.

In the short term, top government officials have set a dangerous tone. They not only failed to publicly denounce anti-press violence, one top official went out of his way to minimise the crimes. Authorities brushed off OAS protective orders, at least one which, if enforced, could have prevented a murder of a journalist. Together, the government’s actions created a climate of lawlessness in which criminals felt perfectly free to kill their enemies.

If the Honduran government wants to remain being treated as a responsible international partner, it must move immediately and aggressively to correct these failures, the CPJ report asserts. It must assign disinterested and trained investigators to these cases where investigations must be transparent and free of conflicts of interest and not under someone else’s influence.

President Lobo and top officials in his government must begin to speak out, in a forceful and timely way, against anti-press violence. His government must respect its obligation and enforce orders of protection for journalists and other social critics.

The international community, according to CPJ, must demand that the Honduran government should immediately undertake these meaningful, measurable, and lasting steps. Calling in the FBI long after murder cases have grown cold and useless is nothing more than saying sorry to a dead man.