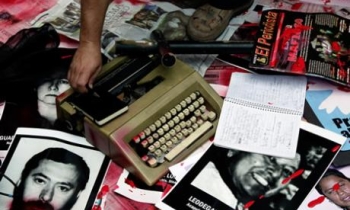

The leak of former CIA agent Valerie Plame's identity continues to spread through the Washington press corps like a toxic plume. As it does, it discredits individual reporters and damages both their news organizations and an entire style of reporting that has come to dominate the way Americans are informed - or misinformed - concerning their government's conduct.

Last week's casualty was the Washington Post's Bob Woodward, who, as it turns out, concealed for 17 months the fact that a Bush administration official (whom he still refuses to name to his readers) leaked Plame's identity to him before the vice president's former chief of staff, I. Lewis "Scooter" Libby - now under indictment for perjury - named the then-covert agent to New York Times reporter Judy Miller and others.

Woodward's disclosure was motivated not by a sudden pang of conscience, as it turns out, but by the sudden necessity of testifying under oath before a federal grand jury. Not only had he concealed this information from his editors and readers for fear of subpoena, but also he had in the interim gone on several television shows to trash the special prosecutor investigating the affair. Moreover, it now emerges, the reporting that went into his last best-selling book, Plan of Attack, involved the submission of written questions in advance to Vice President Cheney, a fact he never bothered to share with the book's readers.

It is fitting that all this should involve Woodward, whose skillful, courageous use of the ur-voice among confidential sources virtually created a whole genre of Washington reporting. It's a style that depends on the cultivation of access to well-placed officials greased by promises of "confidentiality." It still serves its practitioners' career interests, but less and less often their readers or viewers because it's a game the powerful and well-connected have learned to play to their own advantage.

Whatever its self-righteous pretensions, it's a style of journalism whose signature sound is less the blowing of whistles than it is the spinning of tops.

That's why the Washington press corps, whose ranks include so many alleged commentators that you can't spit without hitting one, steadfastly refuses to put the Plame affair and its participants in the context that explains the event. That context is the Bush administration's unprecedented - and largely successful - effort to bend Washington-based news coverage to its ends. The Washington press corps doesn't want to talk about this because it basically puts some of its most admired members in a line of venal patsies. Consider:

Who can forget the administration's payment of nearly a quarter of a million dollars in federal money to the hapless pseudo-columnist and television and radio commentator Armstrong Williams, to promote the President's No Child Left Behind initiative?

Then there was the distribution to local television stations across the country of federally financed, pre-packaged video reports designed to support the administration's educational and energy policy initiatives. The videos were tricked up to look like regular news feeds and apparently ran on numerous small stations whose viewers never were informed that they were watching government propaganda.

Last week, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting's inspector general reported that PBS's former chairman, Kenneth Y. Tomlinson, appears to have violated federal law by trying to force a political slant onto the network's programming. The inspector's report alluded to e-mail between Tomlinson and a White House official. On Thursday, Bloomberg.com reported that "presidential adviser Karl Rove" and Tomlinson "discussed creating a 'conservative talk show and adding it to the public television lineup.' " According to Kenneth Konz, PBS's inspector general, Tomlinson and Rove, President Bush's chief political adviser, also corresponded about "shaking up the agency" and "adding Republican staff."

Placed in this context, Woodward, Miller, Time magazine's Matthew Cooper and NBC's Tim Russert are less tragic figures in a grand journalistic drama than they are sad - but willing - bit players in somebody else's rather sorry little charade.

The administration has adroitly availed itself of the cultural complicity that prevails in a fin de siécle Washington press corps living out the decadence of an increasingly discredited reporting style. As the Valerie Plame scandal and its spreading taint have made all too clear, the trade in confidentiality and access that has made stars of reporters such as Bob Woodward and Judy Miller now is utterly bankrupt.

It still may call itself investigative journalism - and so it once was - but now it's really just a glittering and carefully choreographed waltz in which all the dancers share the unspoken agreement that the one unpardonable faux pas is to ask who's calling the tune.

Tim Rutten (timothy.rutten@latimes.com) writes about the media for the Los Angeles Times.