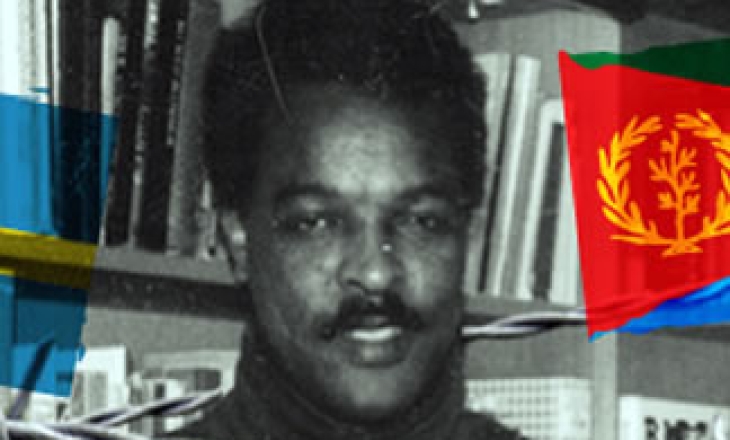

Eritrean authorities must disclose the medical condition and care being provided to jailed journalist Dawit Isaak, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has demanded following unofficial reports saying that he was hospitalised. CPJ pointed out that the well-being of the long-jailed Isaak, an Eritrean with Swedish citizenship, is the responsibility of the government, which has yet to provide any information as to his whereabouts, health, or medical care.

Isaak, 44, a journalist with the now-banned independent weekly Setit, has been detained without charge or trial since September 18, 2001. He disappeared in government custody along with nine other journalists during a brutal crackdown on the independent media and political dissent in Africa's youngest nation. The government, which has swept up other journalists for undisclosed reasons, is believed to be holding 13 reporters and editors in secret prisons. At least one imprisoned journalist, Fesshaye Yohannes, is believed to have died in government custody.

Journalists and activists in Sweden told CPJ that they recently received news that Isaak had been transferred on January 11 from a prison to a military hospital operated by the Eritrean Air Force. They cited a January 13 report, published in the local Tigrinya language on the Switzerland-based Eritrean diaspora website Eritrea Watch for Human Rights and Democracy. The report said Isaac was denied visits and, with the exception of a doctor, had no contact with hospital staff.

Phone calls made to Eritrean Information Minister Ali Abdu on Wednesday and today went unanswered. Eritrean Embassy officials in Washington did not return a phone call seeking comment.

Leif Öbrink, an activist heading a coalition of 10 local and international organisations campaigning for Isaak's release since 2004, told CPJ that several Eritrean sources deemed the January 13 report credible, although it could not be independently verified. The coalition launched the Freedawit website in September 2004 and sends a protest letter to the Eritrean Embassy in Stockholm every Tuesday, he said.

In news reports and an interview with CPJ, the Swedish government expressed concern about the reports. Speaking with CPJ on Wednesday, Swedish Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Cecilia Julin said the government did not have firsthand information on Isaac's condition, but was in the process of "establishing the facts from various channels." The government dispatched a diplomat to Asmara, she said, adding that the case receives "the highest priority" within the administration.

"We are alarmed by reports of the hospitalisation of our colleague Dawit Isaak. The Eritrean government is responsible for his well-being and that of 12 other journalists currently being detained in secret without charge," CPJ Africa Programme Coordinator Tom Rhodes said. "We call on the Eritrean government to free all jailed journalists and finally shed its long-held title as Africa's leading jailer of journalists."

The Eritrea Watch website also reported that on December 13, 2008, Isaak and 112 other political prisoners had been moved to a maximum-security prison in the town of Embatkala, 21 miles (35 kilometers) northeast of Asmara.

The journalist's brother, Esayas, recalled Isaak's words during their last, brief phone conversation: "I'm free. I hope I can come to Sweden for Christmas." This was November 19, 2005, shortly after Eritrean authorities freed Isaak, only to send him back to jail two days later.

Isaak's wife, and three children live in Gothenburg, Sweden. "They're trying to have a normal life," Esayas Isaak said.

With 13 journalists behind bars, Eritrea is Africa's leading jailer of the press and the world's third worst jailer, according to CPJ's annual census of journalists imprisoned for their work.