THE Hamas man cut straight to the point. "Are you scared of being kidnapped?" he asked.

On a dark, cold laneway in the middle of a Gaza refugee camp, it didn't seem like a bad question. But this was a Hamas neighbourhood and Hamas militants do not have a track record in kidnapping civilians.

And then came the man's kicker. "Today I was having coffee," he said pointing towards a main street over the ramshackle homes to the east.

"And people from the Dargmarch family were there with me. They said that they needed to kidnap another Western journalist again, because they were running low on money."

It was Thursday, March 8. Four days later, the BBC's Alan Johnston was bundled into a car by masked gunmen in central Gaza and whisked away. He has not been heard from since, though he is believed to be held by members of the same clan heard plotting in the coffee shop.

The Dargmarch family is one of Gaza's biggest clans. They wield significant power in this tribal society, where a cocktail of feudalism, militant cells, corruption and criminal entrepreneurship subvert the rule of law.

Members of the Dargmarch clan have kidnapped before, most recently nabbing two Italian aid workers in November. The word on the Gaza streets is that the Italians either then, or during an earlier kidnap of an Italian journalist, paid a ransom - a suggestion which, if true, has posed a significant obstacle in securing Johnston's release.

Close to 15 foreign journalists and aid workers have been nabbed in Gaza over the past two years in raids that have often been aimed at alerting the world to grievances about security force salaries, or conditions in the government sector.

A small number - and Johnston would appear to be among them - have been nabbed by mercenary gangs determined to win a ransom. And several others have disappeared for days after falling into the hands of a fledgling group with fundamental Islamic leanings.

Throughout Gaza, the risk of being seized from the streets has been a constant menace to foreigners attempting to work here. But the fear had always been tempered by the reality that if you were kidnapped, you would not end up in an internet video with a knife at your throat.

Your capture was likely to be inconvenient but short, and you would soon be free to tell your story. But the past nine months have brought the end of such certainty. Johnston's seven-day detention and the inflexible demands of his captors pose a new trend in Gaza, where brutal infighting has begun to erode the hold that the tribal system once had on society.

There were once red lines, such as resident correspondents such as Johnston - the only senior international journalist to be based there these days - and groups such as the UN. But that has changed.

On Friday, I drove towards the Erez crossing into Israel, with Stephen Farrell of The Times after we had both spent two days in Gaza. We pulled up on the Palestinian side as two Presidential Guard vans arrived to escort a convoy arriving from Israel.

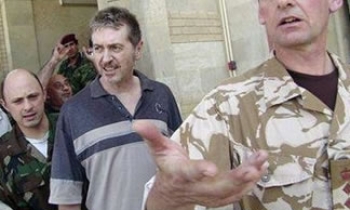

The convoy belonged to John Ging - the most senior UN aid official in the Holy Land. He drove in as we walked out. Five hundred metres up the road, gunmen sprang from a white Subaru and tried to stop Ging and the two other vehicles. His driver sped through the ambush and his attackers responded with an 11-shot volley into his armoured car. He escaped unscathed.

Gaza is not yet Baghdad. But itssteady slide is fast leading it that way.