The chief minister of a major state is a mass murderer. The Prime Minister of India is a small-time manipulator who masquerades as a statesman. The Information & Broadcasting Minister should find better things to do than set up a nipple police. The president of the Congress party is a sleazeball. The chief minister of one of south India’s most important states is a fruitcake.

Shocking stuff? Terrible abuse? Bad taste? Beyond the pale? Well, all of the above, perhaps. But that’s not the point. Every single one of the insults and put-downs quoted above actually appeared in Counterpoint in the years since I first started writing this column in 1992.

(You want to know who’s who? OK. The people so insulted were, in the order listed: Narendra Modi, Narasimha Rao Sushma Swaraj, Sitaram Kesri and Jayalalitha. All were in power when these characterisations appeared in print.)

I always think that one of the great things about India — and one we do not give ourselves enough credit for — is quite how free our press is. Counterpoint has now had three homes (in Sunday, The Telegraph and the HT) and, for a decade-and-a-half, I have been an equal-opportunity offender, taking potshots at people when they are at the height of their power.

And yet, even though the objects of my derision have frequently been angry and agitated, not one of them has used his or her official power to try and muzzle me or to extract any kind of revenge. Nor have my proprietors ever tried to censor me. And, so far at least, I have not become unemployable.

You could argue, perhaps, that sometimes I go too far or that I test the limits of free speech. But you have to give our liberal democracy credit for letting journalists like me say pretty much whatever we want without fear of official retribution. More creditable still, is that most of the politicians I have attacked have not even cut off either my access or that of the publication I represent. They may not like me. But they accept that it is the press’s job to criticise them.

Sceptics sometimes say that we make too much of free speech. How many Indians have access to the media, anyway? Do they really care what smarmy columns people like mine churn out when they are themselves fighting poverty and deprivation and struggling for their very survival?

I accept that there is some merit to this view. But, as the philosopher AC Grayling points out, “Freedom of speech is the fundamental freedom. Without it you can’t have any others. There would be no due process of law because you couldn’t defend yourself; no democracy because you couldn’t argue your case; no assertion of your rights because you wouldn’t be able to explain why those rights are being threatened. All our freedoms balance on this pinpoint.”

So, even the people who are too poor to buy newspapers benefit from freedom of speech, a point that Indira Gandhi missed when she imposed press censorship in 1975. Because there was no freedom of speech, nobody could draw attention to the human rights abuses. And even Mrs Gandhi herself did not find out how angry the poor were about enforced sterilisation until it was too late and she was booted out of office in the 1977 election.

My problem with India’s record on freedom of speech, which is generally excellent despite the aberration of the Emergency, is that, over the last two decades, we have arrived — almost subliminally and without any real debate — at a two-step definition of this vital freedom.

On the one hand, we accept that people have the right to say anything they like (subject to the laws of libel, national security etc) about individuals and voluntary associations. Thus, nobody will pay much attention if I say that Lalu Yadav is a joker or that his RJD comprises goondas. I can say that the Congress is corrupt and venal. I can declare that Mamata Bannerjee is a hysterical fool. I can call the CPM self-righteous hypocrites. And I can dismiss the RSS as fascist chaddiwallahs with knobbly knees.

All of this is regarded as acceptable and makes for energetic public debate. (And yes, you don’t have to be as abusive as I was above — I did that to illustrate how far one is allowed to go.)

The trouble begins when you go beyond individuals and voluntary associations (such as political parties.) If you want to make a remark about a religion, a religious group or a community, then, all notions of freedom of speech suddenly vanish.

Take the example of Salman Rushdie. Midnight’s Children made some offensive references to Indira Gandhi who was Prime Minister at the time. Mrs Gandhi did not ban the book. It was sold freely in India but she took legal action in London (and got the offending passages excised). In contrast, Pakistan banned Shame, Rushdie’s second novel, because it made fun of General Zia-ul-Haq and the Bhuttos (including Benazir who was called Virgin Ironpants). That India’s Prime Minister should not ban a book that personally insulted her while the Pakistanis took the opposite view demonstrates the difference between our societies.

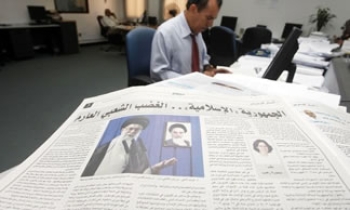

So far, so good. But then, Rushdie wrote The Satanic Verses. Syed Shahbuddin called for a ban on the book (which he had not read) on the grounds that it hurt the sensibilities of the Muslim community. Within days, the Home Ministry headed then by Buta Singh, who probably doesn’t even know how to read, had banned the novel.

Why? Well, because Muslims could be offended by a book which — at that stage — nobody of consequence had even read?

By and large, the media — generally so supportive of freedom of speech — actively backed the ban. Their reason: a community’s sentiments could be hurt.

Ever since, that has been pretty much the norm. A picture of the Koran published upside down in a newspaper because of some production error? Oh, the paper that carried it has to be banned because Muslims might be hurt. A film that suggests Jesus Christ might have married Mary Magdalene and runs to packed houses in Christian countries? Well, Indian Christians want a ban because they say their religion is threatened. A painting of a Hindu goddess by India’s leading artist that some find offensive? Oh, that must certainly be banned (or burnt or torn up) because Hindu sensibilities might be hurt.

Over the last decade, there have been two new worrying developments. The first is that this principle is now extended to history. Textbooks that might hurt the sentiments of a community because they contain the truth about historical events? Withdraw them from circulation and have them rewritten. A scholarly work on Shivaji that some semi-literate goons are told is less than laudatory? Ban the book and ransack the institution where the author briefly worked.

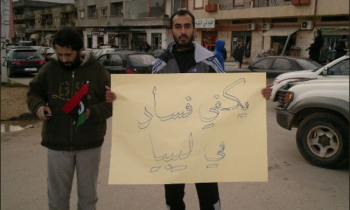

The second worrying development is that this principle of abridgement of free speech on the grounds that communities may be hurt has now gone global. Some Danish cartoonist lampoons the Prophet? Withdraw ambassadors of Muslim countries from Denmark. Issue a fatwa for the head of the cartoonist. And manufacture violence thousands of miles away to protest cartoons that none of the protestors have seen.

An exhibition of MF Husain’s works in London? Threaten to ransack the gallery. Blackmail the organisers into closing the exhibition down because Hindu sentiments may be hurt.

I have never been able to understand why people and societies who are avid defenders of free speech suddenly abandon all their principles when it comes to religions and communities.

Is it because communities represent vote banks? Is it because communities are easier to organise into violent mobs? Or is it because they genuinely believe that the freedom to criticise, lampoon or satirise must be suspended when it comes to religious matters?

If it is the last, then this makes no logical sense at all. Most of the world’s great religions were founded many centuries ago. Not one of them survives in the form it had when it was originally formulated.

All religions have changed with the times and adapted to altered circumstances — without losing the core of their beliefs — only as a consequence of debate, criticism, reform and, yes, art and satire.

If Dayanand Saraswati had not been allowed to criticise idol worship, where would Hinduism be today? If Rammohan Roy had not campaigned against sati, would Hinduism have been better off?

In few areas do we need to value freedom of expression more than in religion. To call Jayalalitha a fruitcake or Narasimha Rao a crook may be useful at the time. In the long run, however, it hardly matters. On the other hand, because religion and rituals go on for centuries, posterity benefits much more from the robust debate on religious issues that only true freedom of speech can engender.

And despite India’s glorious tradition of free speech, we are now busy setting the clock back. Far from encouraging debate, we are rewriting history and preserving religious dogma in formaldehyde. We do it, I suspect, because we believe we are being secular. But secularism, like every other liberal value, is worthless without free speech.

So let’s stop giving in to the protesters and the mobs. And let’s stand up for the freedoms that this country was founded on.

Mail your responses to: counterpoint@hindustantimes.com