BOGOTA, Colombia - It was the sort of scoop any ambitious journalist would jump on. But reporting it could have cost Jorge Quintero his life.

With the help of local officials, a bank manager in the small southwestern Colombian town of Florencia allegedly funneled $11 million in public funds into the foreign bank account of a convicted drug trafficker.

Despite sitting on a pile of incriminating documents, Quintero wrote nothing.

"I wanted to do something but I was afraid," said Quintero, correspondent in Florencia for Colombia's largest daily, El Tiempo. "You know in this town who to mess with and who not."

A year later, when Colombia's slow wheels of justice acted and the criminal ring was dismantled, the story was front-page news.

Journalists across Colombia share Quintero's dilemma. The biggest gag on the country's media often comes from journalists who fear for their lives, especially in far-flung provinces, where the government presence is weak.

Exposing outlaws - be they drug traffickers, leftist rebels or right-wing militias - risks assassination.

Over the past decade, 28 journalists have been killed in Colombia, making it the second-most dangerous country to report from after Iraq, according to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists. Most of the crimes against Colombian journalists, committed by all sides of the country's civil conflict, are never solved.

Only one journalist has been slain over the past two years, a decline President Alvaro Uribe has attributed to the success of his strong-handed security policies. Yet several journalists say there are fewer killings because their work has never been more muzzled.

A CPJ report last year entitled "Untold Stories" found more than 30 radio, TV and print journalists who acknowledged soft-pedaling or turning a blind eye to important news.

Marisol Gomez Giraldo, the national editor at El Tiempo, said her correspondents routinely reject assignments for fear of reprisals. When they do pursue a sensitive story they often report half of what they know and refuse a byline.

Meanwhile, certain conflict zones are virtually off-limits. In the province of Arauca, the paper has been without a corespondent for more than two years.

The result: Journalists increasingly rely on the Colombian military's often inaccurate reports, giving the public a one-sided view of the war.

"It's the most dangerous moment we've ever faced as a profession," said Gomez Giraldo, who as a cub reporter covered the drug-fueled bloodletting in Medellin over the past decade, in which journalists were often targeted. "But you put yourself in the shoes of the journalist in the field, who makes $400 a month, and it's easy to forgive them for not risking their lives."

In the most extreme cases of self-censorship, journalists simply walk away from their beat.

So goes the story of Jenny Manrique, a reporter at Vanguardia Liberal in Bucaramanga, 180 miles northeast of Bogota. After reporting on how paramilitary groups stole relief checks from people left homeless by floods, the 25-year-old reporter received anonymous threats on her mobile phone.

When the threats followed her to her parents' home phone in Bogota, she fled the country. With the help of the CPJ and Colombia's Press Freedom Foundation, she's been living since March in a safe house in Lima, Peru, on a stipend that's less than half of what she earned before taking an unpaid leave of absence from her paper.

Although she hopes to return to Colombia, Manrique's unsure if she'll continue her career.

"I'm not going to let myself get killed over a story, but nor do I want to deceive myself by writing light stories that have no impact," Manrique said.

Authorities, including the president, have at times contributed to the climate of fear.

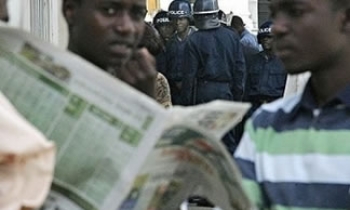

Last week, police detained four journalists accused of helping flame an indigenous protest against a free trade pact with the United States. Although they were later released, two of the journalists complained authorities beat them up and confiscated their camera equipment.

During a radio interview in June 2005, the popular Uribe accused prominent journalist Hollman Morris of collaborating with guerrillas while filming a documentary for the British Broadcasting Corp. in southern Colombia. Uribe later retracted his comments, but Morris claims the verbal attack left him a marked man.

The false allegations against Morris resurfaced this year in a video released by a clandestine organization believed to have ties to paramilitary groups. Morris' stigma of collaborator may have been one reason Bogota's Canal Uno pulled his award-winning TV program, "Contravia," in April.

In response to the threats, the government's DAS secret police - embroiled in a scandal itself for allegedly working hand-in-glove with the paramilitaries - has provided Morris and his family with three bodyguards and an armored car.

"But what use is it if one day they offer protection and the next they spit in my face," Morris said. "All the private security in the world is no substitute for a real political commitment to protect free, journalistic expression."