AMMAN: In a direct challenge to the international uproar over cartoons lampooning the Prophet Muhammad, the Jordanian journalist Jihad Momani wrote: "What brings more prejudice against Islam: these caricatures, or pictures of a hostage-taker slashing the throat of his victim in front of the cameras or a suicide bomber who blows himself up during a wedding ceremony?"

An editor in Yemen, Muhammad al- Assadi, wrote an editorial condemning the cartoons but also lamenting the way many Muslims reacted. "Muslims had an opportunity to educate the world about the merits of the Prophet Muhammad and the peacefulness of the religion he had come with," Assadi wrote. "Muslims know how to lose, better than how to use, opportunities."

To illustrate their points, both editors published selections of the drawings - and for that they were arrested and threatened with long prison terms.

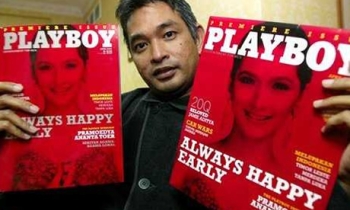

Momani and Assadi are among 11 journalists in five countries facing prosecution for their decision to publish some of the cartoons. Their cases illustrate another side of this conflict, the intra-Muslim side, in what has typically been defined as a struggle between Islam and the West.

The flare-up over the cartoons, which were first published in a Danish newspaper, has magnified a fault line running through the Middle East, between those who want to engage their communities in a direct, introspective dialogue and those who focus on outside enemies.

But it has also underscored a political struggle involving emerging Islamic political movements, like Hamas in the Palestinian territories and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and Arab governments unsure of how to contain them.

"This has become a game between two sides: the extremists and the government," said Tawakkul Karman, head of Women Journalists Without Constraints, a journalists' rights group in Sana, Yemen. "They've made it so that if you stand up in this tidal wave, you have to face 1.5 billion Muslims."

The heated emotions, the violence surrounding protests and the arrests of the journalists have sent a chill through people, mostly writers, who want to express ideas contrary to the prevailing sentiment.

It has threatened those who contend that Islamic groups have manipulated the public to show their strength and that governments have used the cartoons to establish their own religious credentials.

"I keep hearing, 'Why are liberals silent?'" said Said al-Ashmawy, an Egyptian judge and author of many books on political Islam. "How can we write? Who is going to protect me? Who is going to publish for me in the first place?

"With the Islamization of the society, the list of taboos has been increasing daily. 'You should not write about religion. You should not write politics or women.' Then what is left?"

While the cartoons have indeed infuriated Muslims, the regional dynamics underneath the conflict have been evolving over a period of decades, during which leaders have tried to stall the rise of Islamic political appeal by trying to establish themselves as guardians of the faith.

In the end, political analysts around the region say that governments have resorted to the very practices that have helped the rise of Islamic political forces in the first place. They have placated the more extreme religious voices while arresting and silencing more moderate voices, like those of Momani and Assadi.

Jihad Khazen, a prominent Arab columnist for the pan-Arab newspaper Al Hayat, said: "The Islamists wanted to prove their strength. The government replied in kind, saying that we are all Muslims and we care about our religion, and I think the truth was trampled on in the process."

In Jordan, King Abdullah II, who has been trying to control the most extreme religious forces in the region, came out with such a powerful condemnation of Shihan, the paper Momani edited, that even his allies were taken aback.

The newspaper printed three of the cartoons without obscuring them, including one of the prophet in a turban shaped as a bomb with a burning fuse.

Many of the king's supporters said he felt the need to respond as firmly as he did partly because of the rise of Hamas, which won parliamentary elections for the Palestinian Authority, and also to strip the Islamists in Jordan of an issue to rally around.

"What Shihan did was a corruption on earth which cannot be accepted or excused under any circumstances," the Royal Court said in a statement reported by Petra, Jordan's official news agency.

But now there seems to be a growing concern and in some circles a degree of regret for unleashing a wave of anger that has claimed lives.

In Jordan, authorities moved quickly to release the journalists from detention.

In Libya, where spontaneous protests are unheard of, allowing demonstrations against the cartoons seemed a safe bet for the authorities - until the protesters began criticizing the government.

A group of some of the world's most renowned Islamic religious leaders and scholars recently issued a declaration that, though sharply critical of the drawings, sought to rein in the violence and cautioned Muslims against becoming international pariahs. In so doing, they have begun to echo the sentiments of the journalists facing criminal charges.

"We appeal to all Muslims to exercise self-restraint in accordance with the teachings of Islam," the statement said. It added that "violent reactions" can lead "to our isolation from the global dialogue."

To many journalists, proof that Momani and Assadi face charges because of the region's broader political dynamics, and not because of the offensive nature of the cartoons, can be found in Egypt.

After all, Ahmed Abdel Maksoud and Youssra Zahran are free. The two are journalists with the Egyptian weekly newspaper Al Fajr, one of the first Arab newspapers to publish the cartoons. The two wrote a story about the caricatures and reprinted them in October, several months before the conflict erupted, to condemn the drawings.

"The feelings of the Muslims are being exploited for some purpose," said Adel Hammoude, editor in chief of Al Fajr. "Religion is the easiest thing to use in provoking the people. Egyptians will never go out on the street in protest about what happened in the case of the sinking ferry or against corruption or this or that."

That thinking is widespread in Yemen, where three journalists languished in a squalid basement cell, escorted to court by police officers carrying machine guns. It is echoed in Jordan as well, where two journalists await trial.

Momani was to appear in court on Wednesday, while two of the Yemeni journalists were released Tuesday pending their trial. The third was to begin his trial on Wednesday.

Government officials in both countries say the journalists were arrested for having printed blasphemous cartoons. In Jordan, a spokesman said the king felt especially obligated, because his family is a direct descendant of the prophet.

But in Yemen, with presidential elections scheduled for September, many see a more political motive.

"They've now found a good reason to put us here: They say the public demanded it," said Assadi in an interview in his jail cell.

Assadi, who once worked as a part- time correspondent for The New York Times, is the editor of The Yemen Observer, an English-language paper owned by an adviser to Yemen's president. Assadi has been sharing a prison cell with Abdulkarim Sabra, the managing editor of the weekly Al Hurriya, and Yehiya al-Abed, a reporter for that paper.

The three men stand accused of insulting their faith by publishing the images, a crime approaching heresy. In each case the intention was to condemn the drawings, and The Observer put a black X across the picture to obscure the image.

"When I saw all the demonstrations, I thought that Muslims should be able to see what the fuss was all about," said Sabra, during an interview in jail. "I condemned them; I said these drawings don't represent our prophet, burn them."

Michael Slackman reported from Amman and Hassan M. Fattah from Sana, Yemen. Mona el-Naggar contributed reporting from Cairo.