IT'S bad enough when newspaper editorials, Western human rights groups and ordinary American customers condemn your company for bowing to the Chinese dictatorship and contributing to oppression. But when the outrage begins rising, at great personal risk, from dissident voices trapped inside that dictatorship, well, that has to hurt.

Or not.

Yahoo has suffered a good deal of opprobrium after it was revealed last month that, when government officials came calling, the company's Hong Kong division simply surrendered information on a Chinese citizen who had presumably sought refuge, anonymity and a bit of freedom in the bosom of a Yahoo e-mail address: huoyan1989@yahoo.com.cn.

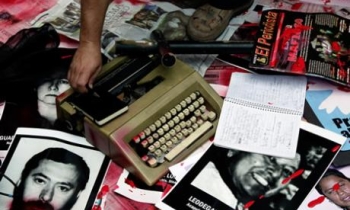

Shi Tao, the journalist using that address, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for sharing with foreigners a message that his newspaper had received from Chinese authorities, warning it not to overplay the 15th anniversary of Tiananmen Square. Yahoo, meanwhile, gets to keep its piece of the gigantic China pie, insisting like most Western companies doing business there that it must abide by the laws of countries in which it operates.

"What if local law required Yahoo to cooperate in strictly separating the races?" asked Max Boot, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, in a widely linked essay for The Los Angeles Times. "Or the rounding up and extermination of a certain race? Or the stoning of homosexuals?"

Jim Etchison, an information technology management consultant from Pomona, Calif., created BooYahoo (booyahoo.blogspot.com) - a site dedicated to urging "freedom-loving citizens of the Internet to discontinue their use of Yahoo services as a result of their oppressive policies."

"I was a happy Yahoo user for about nine years and was so offended by the Shi Tao business that I boycotted them," Mr. Etchison said in an e-mail message. "What begins in China," he said, "will end where I live."

But the most damning missive came just over a week ago, in the form of an open letter to Yahoo's founder, Jerry Yang, from Liu Xiaobo, a Chinese dissident in Beijing who is no stranger to censorship, prison and other indignities associated with the government's mission to stifle free speech and dissent.

"I must tell you that my indignation at and contempt for you and your company are not a bit less than my indignation at and contempt for the Communist regime," Mr. Liu wrote, according to a translated version of the letter appearing on the Web site of the China Information Center (cicus.org), a news and research clearinghouse based in Fairfax, Va. The site was created by the activist Harry Wu, who spent 19 years in Chinese labor camps before coming to the United States.

"Profit makes you dull in morality," Mr. Liu's lengthy and scathing message continued. "Did it ever occur to you that it is a shame for you to be considered a traitor to your customer Shi Tao?"

It's possible that both Congress and the Commerce Department, which oversees exports to questionable regimes, will come to a similar conclusion.

Representative Christopher H. Smith, a New Jersey Republican and chairman of the House Subcommittee on Africa, Global Human Rights and International Operations, was outraged over the Yahoo incident. He has pledged to bring executives of the company to Capitol Hill to explain themselves.

"This is about accommodating a dictatorship," Mr. Smith said in a telephone interview. "It's outrageous to be complicit in cracking down on dissenters."

Representative Dan Burton, a Republican from Indiana and member of the House International Relations Committee, was also concerned. "When people are being put under surveillance and lack the rights to privacy and free thought," Mr. Burton said in an e-mail message, "U.S. companies, the U.S. Congress and the U.S. government must act appropriately and must know when and where to draw the line."

The Commerce Department, under the Export Administration Act, does draw lines where the export of "crime control" equipment is concerned, but Internet technologies do not generally qualify. Last summer, Mr. Burton sent a letter to the Commerce Department asking if it was time to revisit the rules, given that modern software and hardware was being used to track and imprison citizens.

The congressman was "slightly frustrated" at the lack of detail in the response, but companies seeking to cash in on the Chinese Internet boom - its online population of 100 million is now second to that of the United States - might want to keep an ear to the regulatory ground. "Certainly we'll start to look much more closely at this issue to see if revisions are needed," said a senior Commerce Department official, who did not want to be named because such a review is still in development.

And shareholders may rise up and force change where regulation fails to do so. The Paris-based group Reporters Without Borders is preparing a joint statement, with nearly two dozen asset management signatories, calling on Internet businesses to ensure that their products "are not being used to commit human rights violations."

For its part, Yahoo, like Microsoft, Google and Cisco - all of which have come under fire for bowing to Beijing's distaste for search terms like "democracy," or its penchant for filtering and capturing and monitoring communications along its backbone of American-made routers - makes a compelling case when it asks what good it would do to lose access to the Chinese market, or to simply pull up stakes in protest.

"I've always taken the attitude that you're better off playing by the government's rules and getting there," Yahoo's chairman, Terry S. Semel, told attendees of the Web 2.0 conference in San Francisco earlier this month. "Part of our role in any form of media is to get whatever we can into those countries and to show and to enable people, slowly, to see the Western way and what our culture is like, and to learn."

The argument, of course, is that in resisting the demands of the police in China and risking censure, or in wholly divesting from the country on principle, companies would deny whatever fresh air the Internet - filtered and censored as it is - provides there.

But it is also possible that cooperating simply delays an inevitability. "Who needs who more?" Mr. Boot of the Council on Foreign Relations asked. "Do the Chinese need Yahoo and Cisco more than Yahoo and Cisco need China?"

If the answer is the former - as most analysts suspect - and if regulatory oversight and shareholder indignation continue to loom, then a little bit of civil resistance in China might be better for the bottom line than companies currently think.

"What you have said to defend yourself indicated that your success and wealth cannot hide your poverty in terms of the integrity of your personality," Mr. Liu wrote to Mr. Yang of Yahoo. "In comparison with Mr. Shi, your glorious social status is a poor cover for your barren morality, and your swelling wallet is an indicator of your diminished status as a man."