Journalism seems to have recovered its reason for being.

As in the weeks after 9/11, news organizations have plunged into the calamity in New Orleans, with reporters chronicling heartbreaking stories under harrowing conditions in a submerged city. Suddenly, there were no more absurdly hyped melodramas like those of Natalee Holloway or Terri Schiavo, just the all-too-real drama of death and destruction left behind by a monster hurricane.

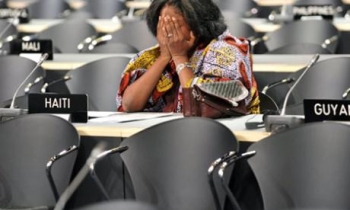

But there were striking flaws in the coverage as well. For the first three days, few journalists mentioned what the pictures made glaringly obvious: that most of the victims of the flooding were poor and black. And in those early days, when reporters were as overwhelmed as anyone by the disaster's magnitude, they seemed more intent on hopscotching from disaster scenes to news conferences than in challenging the tragically slow government response.

Only when the looting, fires, hunger, illness and squalid conditions in places like the Superdome became overwhelming did the coverage turn sharply negative and the reporters' questions more aggressive: Where were the buses, the planes, the food, the police, the promised troops? Where was the planning for a catastrophe that news organizations had been warning about for years?

On television, the frustration boiled over at different times. Fox's Shepard Smith shouted questions at a cop who refused to answer, saying: "What are you going to do with all these people? When is help coming for these people? Is there going to be help? I mean, they're very thirsty. Do you have any idea yet? Nothing? Officer?"

MSNBC's Joe Scarborough reported from Biloxi, Miss.: "What I have been seeing these past few days is nothing short of a national disgrace."

CNN's Anderson Cooper interrupted Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-La.) thanking some of her colleagues, declaring that he had "been seeing dead bodies in the streets here in Mississippi" and that for people to hear politicians exchanging praise "cuts them the wrong way right now, because literally there was a body on the streets of this town yesterday being eaten by rats because this woman had been laying in the street for 48 hours . . . Do you get the anger that is out here?"

This kind of activist stance, which would have drawn flak had it come from American reporters in Iraq, seemed utterly appropriate when applied to the yawning gap between mounting casualties and reassuring rhetoric. For once, reporters were acting like concerned citizens, not passive observers. And they were letting their emotions show, whether it was ABC's Robin Roberts choking up while recalling a visit to her mother on the Gulf Coast or CNN's Jeanne Meserve crying as she described the dead and injured she had seen.

Maybe, just maybe, journalism needs to bring more passion to the table -- and not just when cable shows are obsessing on the latest missing white woman.

The outraged tone continued yesterday when Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff tried to deflect questions about his department's performance on the talk show circuit. "It seems to me this has just been a total failure," Bob Schieffer told him on "Face the Nation."

On "Meet the Press," Tim Russert cited President Bush's comment that no one anticipated the breaching of the New Orleans levees, saying: "How could the president be so wrong, so misinformed?" Russert also loudly lectured Chertoff on the dispatching of evacuees to the city's convention center: "There was no water, no food, no beds, no authority there. There was no planning."

The first to blow the whistle on the initially color-blind coverage was Slate media columnist Jack Shafer, who wrote Wednesday: "Race remains largely untouchable for TV because broadcasters sense that they can't make an error without destroying careers. That's a true pity. If the subject were a little less taboo, one of [the] anchors could have asked a reporter, 'Can you explain to our viewers, who by now have surely noticed, why 99 percent of the New Orleans evacuees we're seeing are African-American?' "

By Friday, the New York Times and The Washington Post were carrying front-page stories on the preponderance of poor and minority victims, many of whom could not afford to leave town in the face of warnings about Hurricane Katrina.

* * *

The press had been sounding warnings about the danger of such storms for years. The New Orleans Times-Picayune, in a much-quoted five-part series in 2002, said: "It's only a matter of time before south Louisiana takes a direct hit from a major hurricane. Billions have been spent to protect us, but we grow more vulnerable every day."

The New York Times wrote later that year that New Orleans is "a disaster waiting to happen" and that a major hurricane could cause the city to "fill up like a cereal bowl, killing tens of thousands and laying waste to the city's architectural heritage. If the Big One hit, New Orleans could disappear." The Washington Post, writing about Hurricane Ivan, said one year ago: "If a strong Category 4 storm such as Ivan made a direct hit, [one expert] warned, 50,000 people could drown, and this city of Mardi Gras and jazz could cease to exist."

So much for the notion that a killer flood was "unimaginable," like terrorists flying airplanes into buildings. This was a case where the press did its job, to distressingly little effect.

Did the undeniable tendency of every network and local TV station to go haywire over each tropical storm and minor-league hurricane contribute to a sense of complacency in New Orleans? Did television simply cry wolf too often? Maybe, although many residents either lacked the financial means to flee or chose to risk staying behind.

Perhaps the least edifying aspect of the media's performance were the commentators who traded charges about who was to blame, even as the floodwaters and death toll were still rising. National Review columnist David Frum blamed liberals who contended that "the disaster was caused by the Bush administration's failure to protect the environment from global warming . . . no, no, it was caused by the administration's refusal to manipulate the environment by funding more levees to control the Mississippi River . . . it's Iraq, no it's budget cuts, no it's wetlands, and on and on and on.

Good God, what is wrong with these people? Will they ever learn to see somebody else's misfortune as something more than their political opportunity?"

But some on the left accuse conservatives of exploiting the tragedy, while others keep their focus on the war. Liberal blogger Markos Moulitsas, at Daily Kos, says America is a place "where an elective invasion of distant lands is possible, but airlifting food and water to stranded refugees inside our own borders is not. Where the top Republican in the House kvetches about rebuilding New Orleans while happily funding the rebuilding of Iraq. Seemingly without worrying himself that reconstruction estimates for New Orleans -- $25 billion -- equals just three months of funding for the Iraq quagmire."

Maureen Dowd made a similar argument in her New York Times column, saying money for Louisiana levees was "depleted by the Bush folly in Iraq," which has also drawn "30 percent of the National Guard."

But some criticism has crossed ideological lines, with the conservative Washington Times saying that Bush "risks losing the one trait his critics have never dented: His ability to lead, and be seen leading."

Kudos must be given to the bloggers who have organized aid drives for Katrina's victims; Insta-pundit's Glenn Reynolds listed dozens and their recommended charities.

The broadcast networks deserve credit for planning their fundraising specials, though one has to wonder how big a disaster it would take for them to abandon their lucrative entertainment shows and provide wall-to-wall news coverage, as they once did before fobbing off such matters on cable.

For a hopeful period after Sept. 11, 2001, it seemed the media were ready to relegate celebrities, gossip and tabloid tales to the margins and launch a new era of seriousness.

That, needless to say, did not last. The challenge for journalists now is how long they will stay with the New Orleans catastrophe as it turns into a long, painful slog of rebuilding and resettlement.

Howard Kurtz hosts CNN's weekly media program.