One night in mid-November, several dozen journalists gathered in the Tribeca loft of the writer Jacob Weisberg to celebrate the publication of The Slate Diaries, a collection of journal entries by assorted contributors to the online magazine. Among those in attendance were Michael Kinsley, the editor of Slate and a columnist for The Washington Post; Hendrik Hertzberg, a staff writer for The New Yorker; John Tierney, a columnist for The New York Times; Jonathan Alter, a senior editor at Newsweek; Philip Weiss, a columnist for The New York Observer; Michael Hirschorn, the editor of Inside.com, a Web site about the media world; and Mickey Kaus, a contributor to Slate. As the guests nibbled on chicken sate and sushi rolls, they marveled at the apartment, with its immense living room, soaring ceilings, staircase leading to the second floor, and balcony overlooking the first. Weisberg, Slate's chief political correspondent and a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine, and his wife, Deborah Needleman, an editor at large at House & Garden, had moved in just a few weeks earlier. At the party there was much speculation as to how much of the purchase price had been covered by Weisberg's recent deal to write the memoir of Robert Rubin, for which the former treasury secretary was to receive a $3.3 million advance from Random House.

My first thought on hearing of the reception was, Why wasn't I invited? In the New York media world, attendance at such events is a good measure of one's status, and so I naturally felt mortified by my absence. On the other hand, had I attended the event, I would have been less inclined to write about it in connection with the New York media elite. Those who actually belong to that elite generally don't like to acknowledge its existence, much less its influence.

Consider, for instance, the case of Randall Rothenberg. A columnist for Advertising Age and a former editorial director at Esquire, Rothenberg would seem a card-carrying member of the New York media elite. But after appearing as a guest speaker on the subject at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, he wrote a column pooh-poohing the whole idea. If there ever was such an elite, "it's dying," he wrote, and "New York itself is losing whatever primacy it once held." The cause, Rothenberg argued, was the rise of the new communications technology, which, by fragmenting the media's audience, and the media themselves, had weakened the influence of individuals over content. Today, he went on, the New York media elite "are not leading anything. They are responding to sly humor from The Onion in Madison, Wisconsin; to politics-and-sex dished out by Salon in San Francisco; to clannish gossip, assembled by Romenesko in Minnesota; to Hollywood box scores, tallied by Aintitcoolnews.com in Austin, to TV. And those who say otherwise . . . are eliting you down the garden path."

Sorry, Randy, but you've been spending too much time online. Yes, plenty of journalists have bookmarked those sites, but this winter the cash-strapped Salon had to lay off staff, again, and Jim Romenesko's site is little more than a clipping service of established news organizations. And, since Rothenberg's column appeared, The Onion has decided to move its headquarters from Madison to, yes, New York, which, its publisher explained, is "the best place to create the funniest stuff and find the best comedy writers." With media dot-coms folding by the dozen, and with AOL's recent merger with Time Warner, surely the big news about the Internet is the growing consolidation taking place there. In a recent article in The New York Review of Books, James Fallows convincingly argued that most of the grand pronouncements made about how the Internet was going to transform life in America have proved overblown, and I think this applies to the great democratization foretold for the news media.

In fact, a strong case can be made that the New York media elite -- buoyed by the boom on Wall Street -- are more powerful than ever. They are, however, a transformed elite. For that same Wall Street boom has caused some fundamental changes in the ideology of New York journalists and how they cover the world. All through the 1990s, after all, the stock market has been the center of the universe, and the New York media have felt its gravitational pull from very close range.

There was once a time when the power of the New York media elite was on the wane -- in the 1980s. The Reagan Revolution was rising, the Rust Belt was corroding, and New York, like many cities, was reeling from the twin plagues of crack and crime. In TV news, the top innovator was CNN, based in Atlanta, while USA Today, in Arlington, Virginia, was striving to become "the nation's newspaper." Meanwhile, Washington was emerging as the nation's new intellectual center, a development symbolized by Irving Kristol's decision to move there from New York. "NYC, RIP," The New Republic gloated on its cover in 1988. In those days, TNR was a must read among the literati, and Washington's Cokie Roberts was TV's "it" girl.

Today, the Washington media elite -- their reputation dimmed by shoddy performance during the Monica affair and by the endless squawk of all those capital-gang talk shows -- seem to have lost some of their luster. And as New York City has rebounded, so, too, has New York's news industry. The struggling CNN has been absorbed into Time Warner, and the dynamism in cable news has shifted to the Fox News Channel, based in Manhattan, and MSNBC, in nearby New Jersey. Time Warner is building a new headquarters in Columbus Circle, and Reuters is matching it in Times Square. Condé Nast has already moved into its own Times Square tower, featuring a seven-story-high NASDAQ video sign and a swank cafeteria designed by Frank Gehry. The Times Square news zipper, meanwhile, is operated by Dow Jones, publisher of The Wall Street Journal, the nation's top provider of financial and economic news.

The organization that gave Times Square its name is planning to shift to plusher digs on Eighth Avenue. While changing location, though, The New York Times will retain its undisputed status as the nation's top news organization. Under Joe Lelyveld, the paper, with twenty-nine foreign bureaus, a crack national team, unmatched cultural coverage, and a nimble satellite printing system that allows it same-day delivery across the United States, dominates the national news chain like never before. Its front page -- the bulletin board for the eastern establishment -- is able to force a story onto the national agenda like no other space. Just ask Wen Ho Lee.

Well, you might ask, so what? What difference does it make to the average news consumer that New York is home to so many top news organizations? It means, first of all, that the city, and events occurring there, get special treatment. Would Newsweek have put the Yankee-Met World Series on its cover had it been based in Chicago?

By the same token, the media's New York-centricity means that some important stories get neglected. Because the city is so highly urbanized and so well served by mass transit, for instance, issues affecting suburbia, such as sprawl and traffic congestion, tend to get short-changed. Similarly, the huge influx of Mexicans to the U.S., so visible in the west, has been neglected. Jews, heavily concentrated in New York, get more space than their numbers would seem to warrant, at least in The New York Times, where no minyan in the world seems too small to write about.

Such parochialism, however galling to Americans west of the Hudson, is but one effect that the New York setting has on the journalism that is produced there. Traditionally, the main charge leveled against the eastern media elite is that they have a liberal bias. This complaint dates back to the days of Nixon and Agnew, but it was first fully catalogued in 1986, when Robert Lichter, Stanley Rothman, and Linda Lichter came out with their book The Media Elite. Most journalists vehemently reject the notion of bias. A "stale stereotype" is how many feel about the label, Howard Kurtz wrote in The Washington Post last September. Kurtz noted how tough the press has been on Bill Clinton. Others have pointed to the rough treatment Al Gore got in the course of his campaign. Yet a presidential campaign seems a less-than-ideal occasion for evaluating bias in the media. A more reliable test, I think, is the day-to-day coverage of controversial issues. And here, I think, it's undeniable that the press does list to the left.

Take, for example, the death penalty. In recent months, national news organizations have produced a flood of stories questioning how the death penalty is administered in this country. These accounts have documented the poor legal representation available to death-row inmates, the extra-harsh treatment minorities generally receive, and, most dramatically, the growing number of innocent people who have been condemned to death. As an opponent of capital punishment, I applaud such stories. Yet I also believe that they lean toward one side of the issue, and that the coverage would be enhanced if more attention were paid to, say, the families of murder victims and the ordeal they must endure.

Similarly, in the case of gun control, the press has run countless stories on the lax regulation of gun shows, the ease with which criminals can get firearms, and the political clout of the National Rifle Association. Comparatively few articles have probed the tactics of Handgun Control or explored the argument that allowing citizens to carry concealed weapons can deter crime. Does every member of the media think this way? Of course not. But there is a prevalent mindset that reinforces itself through peer and social pressure. This would be true anywhere, but it is magnified by the concentration and intensity of media life in New York. A similar elite slant can be detected, I think, in the coverage of abortion, gay rights, the environment, affirmative action, school prayer, and the other hot-button issues of the culture wars.

But that's only half the story. The other half concerns economic issues. And here, I think, elite journalists have increasingly come under the sway of the markets. They're not alone, of course. The boom on Wall Street has turned factory workers into investors, c.e.o.s into heroes, and logos into icons. Still, the market fever has been particularly intense in New York, and this has affected the media elite in numerous ways.

Most immediately, the rise in the Dow has boosted the living standards of many journalists. In Manhattan newsrooms, reporters and editors regularly click onto the Web to see how their portfolios are doing. They subscribe to Saveur, drink fine wines, and vacation in Europe. "I hear more talk at literary cocktail parties about Michael Eisner's stock options than about the new Don DeLillo," James Atlas observed in a notorious 1998 New Yorker article. In it, he complained about his financial state despite owning a summer home in Vermont and a comfortable apartment in Manhattan and sending his son to private school. "You never have enough," a successful writer tells Atlas, who confesses his longing for a Range Rover.

Such material preoccupations are reflected on the life-style pages of the nations' newspapers and magazines. The Wall Street Journal's "Weekend Journal" section, for instance, reads increasingly like Town & Country. A travel column on landmark hotels in London described how, at the Lanesborough, "elegantly dressed doormen in dove-gray morning suits and bowler hats usher you through the imposing arched entry into an elegant, sweeping marble lobby warmed by a crackling fireplace." Rooms at the hotel range in price from $360 to $5,700 a night.

The frenzy on Wall Street has further fed an explosion in business coverage, most of it reported from the perspective of investors. Newsstands brim with new publications like Fast Company and Smart Money, Forbes ASAP and The Daily Deal. David Denby, who in 1996 came out with Great Books, a loving look at the Western literary canon, is now writing a book about investment, technology, and greed. In The New Yorker last year he wrote, "I have decided that I want -- I need -- to make a million dollars in the stock market this year." Even Eric Alterman, media critic for the left-leaning Nation magazine, has begun writing a column (called "Cash Values") for Worth magazine.

If the market has become the center of the universe, the "new economy" has, at least until recently, been the center of the markets, and the media's coverage of it has suffered from irrational exuberance. In 2000, for instance, The New Yorker published two special "Digital Age" issues (this in addition to a "Money" issue). On Mondays, The New York Times devotes its Business Day section to "The Information Industries," and no new-media Web site seems too small or insignificant to merit coverage. Fortune magazine, that Lucean model of sober business reporting, has essentially remade itself into a hip high-tech organ, the better to compete with such ad-thick hatchlings as The Industry Standard, Red Herring, and Business 2.0, all of which focus on the business of the Internet.

In many respects, the emphasis on the Internet seems natural. The rise (and partial decline) of a powerful new communications technology is significant and makes for good copy. But the sheer quantity of the coverage, and its often-breathless tone, suggests that other factors are at work. For one thing, media coverage of the Internet no doubt helps attract all those new-economy ads that have been fattening so many publications. Another factor is the personal stake that many New York journalists have come to have in the Internet.

In the early 1990s, when the Internet was just emerging, most elite journalists saw it as a threat. The new economy was based in the west, in Silicon Valley and Seattle, and it was staffed by technogeeks laboring away on abstruse software packages. The leading tribune of this world was Wired, which, with its staunch libertarianism, nerve-jangling graphics, and prophetic tone, grated on eastern sensibilities. As the Internet took off, however, and the need for content grew, its center of gravity shifted east, and the New York-based journalists began to sense its possibilities. A key moment came in 1997, when Jim Cramer, the investment and financial writer, started TheStreet.com, an insider's guide to the markets. In the early flush of the dot-com surge, it did staggeringly well. And, in the few years since, the media elite have progressively colonized the Net.

Consider that reception for The Slate Diaries: Slate, of course, is distributed online. Though it's based outside Seattle, many of its writers live in New York, and their salaries are paid for by Slate's owner, Microsoft. Microsoft, in turn, is co-owner (along with NBC) of MSNBC. Some of the guests at the party contribute to MSNBC.com. Meanwhile, Michael Hirschorn, a veteran New York editor, has joined with Kurt Andersen (formerly of Time, Spy, and The New Yorker) to launch Inside.com, the one-stop Internet site for news and gossip about the media world. Mickey Kaus, formerly a writer for The New Republic, has started his own Web site, kausfiles.com, on which he posts his political musings; the liveliest of them are picked up by Slate. And so on.

In covering the Internet, then, New York journalists are often writing about their own world. And, not surprisingly, their appetite for detail seems boundless. A good example occurred in late November, when The New York Times, in Business Day, ran a long takeout on the future of the e-book. As the writer, David D. Kirkpatrick, noted in his lead, the e-book seems a long way from becoming a reality. "Few people have ever read a whole book on a screen," he wrote. "No one knows how many people will ever want to." The one independent analyst cited in the piece said that consumer research "indicates very little interest in reading on a screen." This, however, did not keep Kirkpatrick from devoting 3,500 words to the subject, most of them relaying in minute detail the machinations of various New York authors, publishers, and agents.

Overall, from the amount of media coverage the new economy has received, you'd think that it accounts for a large portion of the nation's GDP. In fact, according to a report issued last summer by the U.S. Department of Commerce, IT (information technology) industries "still account for a relatively small share of the economy's total output -- an estimated 8.3 percent in 2000." As of 1998, those industries employed only 6.1 percent of American workers. And despite all the stories about Amazon, e-Bay, and the rest, online retail sales make up less than one percent of all retail sales in the United States.

In short, the media's e-mania has produced a skewed picture of the U.S. economy. But the distorting effects of its obsession go deeper. In the process of writing about digital start-ups and IPOs, Cisco and Oracle and the rest, journalists have become increasingly enthralled with entrepreneurship, deal-making, and the free-market system in general, to an extent that makes tough and clear-eyed analysis difficult.

Consider, for example, the career of Michael Lewis. In 1989, Lewis made a name for himself with Liar's Poker, a biting send-up of the greed on Wall Street based on his experience as a bond trader for Salomon Brothers. "The American financial system," Lewis wrote, had become "wild, reckless, and deeply in hock." Ten years later, Lewis came out with The New New Thing, a profile of Jim Clark, the founder of Netscape, and it is full of wonder -- at Clark's restless mind, his multibillion-dollar fortune, and the Silicon Valley culture that nurtured him. "The business of creating and foisting new technology upon others that goes on in Silicon Valley is near the core of the American experience," Lewis writes. "Silicon Valley is to the United Sates what the United States is to the rest of the world. It is one of those places, unlike the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but like Las Vegas, that are unimaginable anywhere but in the United States. It is distinctively us."

Or consider Jacob Weisberg -- the host of that loft party and one of the nation's top political writers -- and his agreement to write the memoir of Robert Rubin. He is not writing about Rubin, keep in mind, but with him. Jacob (a friend of mine) says that his arrangement with Rubin "is not atypical of the relations that journalists have with public figures from time to time. And it's a one-time thing. A case can't be made that this represents a softening on my part." No doubt Weisberg will continue to produce incisive journalism, but I don't see how his new partnership can help but affect the way he writes about subjects like the world economy, of which Rubin is an architect.

Even without money being exchanged, most journalists have been gushing in their coverage of the former treasury secretary. While Rubin and other economic policymakers do deserve some credit for the percolating U.S. economy, journalists -- mesmerized by the Dow -- seem to have lost their ability to scrutinize their actions with the necessary skepticism.

A good example is the cover story Time ran on February 15, 1999. Titled the three marketeers, it looked at how Rubin, Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, and deputy treasury secretary Lawrence Summers had responded to the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998. By then, many financial analysts had concluded that the Clinton administration had made several key blunders in responding to the crisis, aggravating its severity. Time glossed this over, offering a single paragraph halfway through that laid the blame solely at the door of the International Monetary Fund. It cast the three U.S. officials as "economist heroes" and "the committee to save the world." Correspondent Joshua Cooper Ramo wrote:

What holds them together is a passion for thinking and an inextinguishable curiosity about a new economic order that is unfolding before them like an Alice in Wonderland world. The sheer fascination of inventing a 21st century financial system motivates them more than the usual Washington drugs of power and money. In the past six years the three men have merged into a kind of brotherhood, with an easy rapport.

The three officials, Ramo went on, "have outgrown ideology. Their faith is in the markets and in their own ability to analyze them." This inability to recognize that putting such faith in the markets is itself a form of ideology shows the extent to which the boom on Wall Street has dulled the media's analytic ability.

This failure is nowhere more apparent than in the coverage of the developing world, or "emerging markets," as journalists (following the lead of Wall Street) like to call them. When Bill Clinton visited Vietnam in mid-November, for instance, The New York Times ran a series of background pieces. Vietnam is an overwhelmingly rural society with a per capita income of $370 a year, but the Times pieces tended to focus on a narrow, privileged slice of urban society. nascent internet takes root in vietnam, ran the headline over one of them, about an entrepreneur's efforts to market the Internet in Vietnam (even though a mere 100,000 of its 79 million residents have access to it). Accompanying the piece was a photo of a beautiful young woman demonstrating the Internet to a group of eager youths at a communications fair in Hanoi.

ABC's World News Tonight began its own background piece with a clip of another beautiful woman, a worker singing a revolutionary anthem. The segment then cut to a disco, where a group of beautiful people was shaking it up on the dance floor. "You can still find a few young Vietnamese performing the old revolutionary songs," correspondent Mark Litke declared, "but when the uniforms come off, Vietnam's post-war generation rocks to a very American beat." From the disco, Litke took us to a Nike factory outside Ho Chi Minh City, where we were shown around by a company executive. The pay at the factory is only $50 a month but, Litke hastened to note, that is well above the national average. "These jobs are extremely attractive," the Nike official assures us.

Perhaps the workers at the Nike plant do like their jobs. We can't say for sure, however, since we never hear from any of them. Certainly Nike's presence overseas has been controversial, with many questions raised about the working conditions at its factories. Taking us inside that debate, however, would have required stepping outside the box and looking searchingly at the impact of global capitalism on Vietnam, but that is something Litke (like the Times correspondents) seemed reluctant to do.

It's important not to overstate this. National news organizations, led by the Times, the Journal, and The Washington Post, continue to offer much incisive reporting on such issues as human rights abuses, environmental degradation, and the crushing effects of third-world poverty. At home, too, these newspapers have attempted to afflict the comfortable with accounts of the millions of Americans who have been left behind by the boom. But these stories can get lost amid all the hoopla over the market and the Internet, luxury hotel suites and $400 shoes.

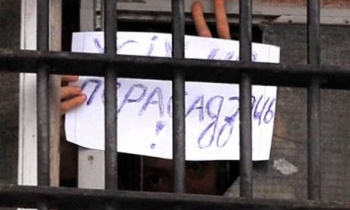

On the same day that the Times offered its endless account about the future of the e-book, for instance, it ran a brief AP item about a rally in Seoul, South Korea, at which thousands of workers protested corporate reorganization plans that they feared would lead to sweeping layoffs. Only 138 words long, the article offered no further explanation. Looking up the original AP story on Nexis, I discovered that the rally had been called in support of workers at the state-run power company, which the government planned to break into several units and sell off -- part of a broader effort to shut down or sell fifty-two companies. "The move shocked tens of thousands of workers who work for those and other financially shaky companies," the AP reported. The policy, it added, resulted from government promises to the IMF to restructure its finances in return for a $58 billion bailout loan. Caught up in the struggles of the electronic book, the Times found none of this fit to print.

As a result of such priorities, the media elite are muffing what is perhaps the biggest story of the day: globalization. The growing integration of the world economy, the dismantling of international trade barriers, the blink-of-an-eye flow of capital between countries, the rapid technological changes that are everywhere creating new classes of winners and losers -- U.S. news organizations have done a poor job of explaining it all. During the past election, probably few elite journalists voted for George Bush, but probably even fewer voted for Ralph Nader or at least listened to his complaints about the direction of the new global order. And this is reflected in the coverage. The press may be biased in favor of abortion rights, gun control, and affirmative action, but it's also partial to Dow Jones, Goldman Sachs, and Robert Rubin.

But there are some signs of hope. With the recent troubles in the market, some small cracks are beginning to appear in the media's bond to Wall Street. All these assumptions about the glamour of the new economy, the sclerosis of the old, and the virtues of untrammeled capitalism are being called into question. entrepreneurs' 'golden age' is fading in economic boom, The New York Times declared on its front page in early December, atop a story noting that, despite all the hoopla about the growth of entrepreneurship in the United States, the number of self-employed Americans outside agriculture had actually declined between 1994 and 1999, the first five-year span in which that had occurred since the 1960s. Here and there, other such pointed analyses are beginning to appear. Are the media elite perhaps heading for their own market correction?

Michael Massing is a contributing editor to CJR. He is the author of The Fix, about America's drug war, published in paperback last year.