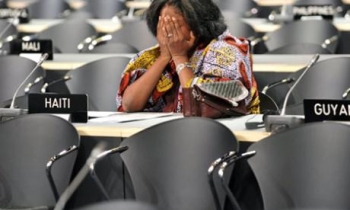

The first anniversary of a landmark UN Security Council call for an end to the killing of journalists worldwide has passed—and the deaths continue to rise.

The International News Safety Institute (INSI) counted 171 news media fatalities in 2007, outstripping the previous record of 168 set in 2006. Indeed, each year since the millennium has set new levels in blood.

- What is happening? On December 8, Gerardo Israel Garcia Pimentel, a 24-year-old reporter for the Mexican newspaper La Opinion, was chased by hit men to the top floor of a hotel in which he lived and shot more than 20 times with a rifle and a hand gun. 45 spent shells were found next to his body.

- On October 24, a gunman stepped out from behind some trees on a busy thoroughfare in Osh, Kyrgizstan, and shot to death 26-year-old Alisher Saipov, one of the top reporters in the country, as he waited with friends for a taxi. He was first shot in the leg and when he fell, the gunman fired two shots to his head—apparently the first contract killing in a country hitherto known for relative media freedom.

- More than 160 attacks on the news media were registered in 2007 in the Democratic republic of Congo, up nearly one third over 2006, a local rights group, Journalists in Danger (JED), said. Nearly 90 per cent of the murders and threats were committed by the military or different security services, it said.

- On November 27, Sri Lankan army aircraft struck the Voice of Tigers radio station near Kilinochchi in the north of the country, killing at least three civilian news staff. The attack—which tipped 2007 over into all-time record numbers of news media deaths—was widely condemned as a war crime.

Repeat these incidents over and again, changing only names, places and dates, in 36 countries in the course of the year since the UN Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1738 on the safety of journalists in conflict on December 23, 2006.

Action by the world's highest political institution was a milestone for those of us embarked on a seemingly endless mission to protect the lives of journalists and support staff working on dangerous stories.

It was more than a gesture to the importance of journalists to democracy. The resolution demanded action by member states: an end to violent attacks on the news media and an end to impunity for those who kill journalists. The resolution had one big hole in it. It addressed solely the safety of journalists in armed conflict.

After a two-year inquiry into news media deaths around the world over the 10 years 1996-2006, which recorded 1,000 deaths, INSI reported the majority were not daring war correspondents but local reporters and editors who died in their own countries in peacetime as they tried to uncover crime, corruption and other political, social and economic ills. Most were murdered and in 9 out of 10 of cases no one ever faced justice.

In January 2007 the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe passed Resolution 1535 on the safety of journalists. It addressed the violence directed at journalists in peace and war. Yet, more than ever, journalists and other news professionals continue to die trying to cover the story.

Many journalists are murdered and kidnapped by elements beyond the reach of any international body or bodies of law. Insurgents are responsible for the great majority of the 236 news media personnel who have died since 2003 in Iraq (as on January 3, 2008).

There was a time when all parties to a conflict found journalists useful to tell their stories. No longer. The internet provides a ready platform to get words and video around the world untouched by argument or criticism.

The "war on terror" rallying cry of "you're either with us or against us" has been taken up with great gusto by all. No one any longer seems much interested in the journalists' plea to be able to tell "both sides of the story". Some find it antagonising.

The Sri Lankan government sees a Tamil radio station as an enemy, just as NATO did when its forces bombed the Serb radio and television headquarters in 1999, during the Kosovo war, killing 16 civilian employees.

US forces in Iraq are deeply suspicious of Iraqi journalists, especially if they work for Arab networks such as Al Jazeera, as is the Israeli army with Palestinian cameramen. Shimon Peres said at the start of Intifada 2 that a camera can be more dangerous than a gun. Such careless words can send a dangerous message to twitchy troops on the ground.

Had Associated Press cameraman Bilal Hussein been carrying a gun instead of a camera in Iraq, he may well have been free by now thanks to America's shifting local alliances, rather than languishing without charge in a US military jail for almost two years.

What can be done?

Well-meaning resolutions passed by international bodies must be lived up to in letter and spirit. Legitimate governments must show the way by prosecuting the killers of journalists at least as efficiently as they pursue other murderers.

Impunity is the most urgent threat facing free reporting worldwide. Murder becomes a cheap, risk-free and extremely effective form of censorship, getting rid of the immediate problem and intimidating others into silence.

The latest statistics for journalist deaths, issued by INSI on January 3, show a slight fall in the number of suspected murders in 2007. But it is too soon to tell if this is the start of a trend or merely a blip in the steady increase recorded over recent years.

Governments, especially democracies, must set a clear example to the murderous by their own actions, especially in showing more tolerance of opposing voices, even, or perhaps especially, during the "war on terror".

UNESCO Director-General Koichiro Matsuura, long a staunch advocate of freedom of expression and journalist safety, reminded the Sri Lankan government that military strikes on civilian media contravene the Geneva Convention which requires the military to treat media workers as civilians. In an aside that might usefully be noted by other states, big and small, he added that anyhow killing media personnel did not "help reconciliation."

Undoubtedly, 2007 has been terrible. But there have been some encouraging moves which, if followed through honestly and constructively, just conceivably could make the year a turning point.

Generally, awareness of the gravity of the situation—and the threat to the free flow of information on which free societies, prospering economies and good governance depend—has risen around the world.

On November 30, responding to an alarm sounded by the International Committee of the Red Cross, seven countries—Australia, Britain, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany and the United States—pledged to improve safety for journalists covering conflicts and to combat impunity for those who target reporters.

A week later, the third World Electronic Media Forum (WEMF3), meeting in Malaysia, took up the issue and recommended the UN Secretary-General appoint in his office a Special Rapporteur on the Protection of Journalists, to report to him annually on progress made by states in implementing Resolution 1738. The forum, which brought together broadcasters, journalists, policy makers and academics, also urged states to implement the resolution and end impunity.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon told me at UN headquarters that he stood squarely behind moves to improve journalist safety. Resolution 1738, he said, was a key milestone but just the beginning of a longer struggle to address the problem of impunity. He promised his unyielding commitment to the creation of the necessary security and political conditions to enable journalists to work free from danger.

He noted the opportunity presented by the 60th anniversary next year of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 19 states: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom … to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media, regardless of frontiers."

In addition to moves by the international community, a growing number of news organisations are demonstrating awareness of their duty of care to staff and freelancers, providing professional safety training and modern protective equipment.

BBC correspondent Alan Johnston was freed in July from 114 days captivity in Gaza after a great campaign boosted by the support not only of journalists but—most gratifyingly for journalists resigned to being widely unloved—of thousands of ordinary people around the world.

The INSI global survey heard testimony that journalists must get societies on side if their security is to be assured. More people need to be persuaded that journalism, at its best, is a noble profession, vital to the workings of true democracy.

They have much to do.

As this bloody year (2007) drew to a close, a BBC World Service poll of more than 11,000 people in 14 countries found that 40 per cent said social harmony and peace were more important than a free media.

Journalists clearly need to do more to get their societies behind them—to persuade their audiences that there can be no real security without freedom of expression and that there can be no free expression where journalists are murdered.

In the final analysis, free reporting is the only safeguard against the knock on the door in the middle of the night.